The Caribbean monk seal is an extinct species of seal that used to live in the Caribbean Sea and its islands. It was also called the West Indian Seal or the sea wolf. It gone extinct due to hunting for oil and overfishing in their food sources. The last sighting of this species was in 1952 at the Serranilla Bank between Nicaragua and Jamaica.

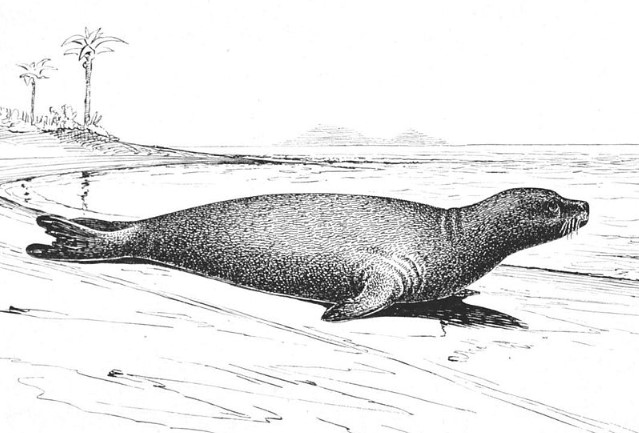

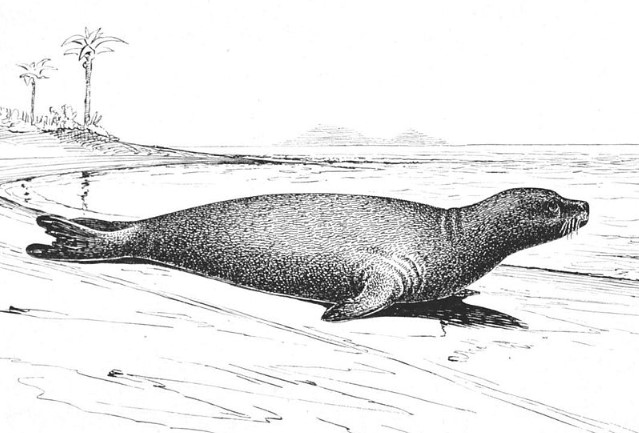

Caribbean monk seals had large, robust bodies and a distinctive head and face. Like other monk seals, it had a rounded head and an extended, broad muzzle. When compared to the body, the animal's foreflippers were relatively short with little claws and the hindflippers were slender. Adults were brownish and/or grayish in color with the underside lighter than the back. The juveniles were more pale and yellow than the adults. Like Mediterranean monk seals, the males were probably slightly larger than the females. They are also known to have algae growing on their backs, giving them a more greener color, like Hawaiian monk seals.

The Caribbean monk seal is one of three species of monk seals. The other monk seals are the Hawaiian monk seal and the Mediterranean monk seal. It mostly ate fish and crustaceans like spiny lobsters. Caribbean monk seals had a long pupping season, which is typical for pinnipeds living in subtropical and tropical habitats. In Mexico, breeding season peaked in early December. Its lifespan was approximately twenty years. Like other seals, this extinct species was sluggish on land. It’s lack of fear to humans and a curious nature led to hunters taking advantage against them.

When Spanish explorers traveled from Europe, hunters from these countries killed these seals. They were targeted for their meat, hide, fur, and oil in their blubber. They were also captured for display in zoos and killed for museums. Overfishing also happened in the reefs that sustained the Caribbean monk seal population. With no fish or mollusks to feed on, the seals that were not killed by hunters for oil died of starvation.